What Makes Some Art More Famous than Other Art?

According to Oxford Languages, fame is defined as “the state of being known or talked about by many people, especially on account of notable achievements.”

So, if we apply that to art, that means a painting that is “talked about by many people” must be famous. Fame does not mean, however, that the painting has to be of notable achievement. It could be, but doesn’t have to be.

What is it then? What causes some art to be considered more valuable or famous than other art?

We are taught from a young age that the more skilled you are, the more you will be rewarded and admired and valued (which could be considered to be equivalent to fame). But, that just simply isn’t the case in the art world. Rather, the impact the art has had on society is the true determination of its value and worth, not the skill needed to create the art or the quality of the artwork.

Sometimes, though, the fame of the individual artist can increase the value of their artwork, even if a particular piece of their art has not made a substantial impact on society itself. Consider how occasionally in the news you might see a headline that says something like, “old painting in woman’s attic might be a Van Gogh original.” Then, suddenly, this painting that was worthless is now worth millions simply because Van Gogh’s paintbrush touched the surface of the canvas. Upon a quick Google search I came across a similar, real article. An article recently published from The Smithsonian has a headline of, “A Connecticut Mechanic Found Artwork Worth Millions in a Dumpster.” You can read the whole article by clicking here.

On the flip side, one work of art could bring fame to an artist, almost like the “one hit wonders” of the music world. Whether it be for the painting or the artist, it really boils down to a popularity contest.

Let’s explore some tangible stories that relate to this argument of connecting art’s value to its impact on society.

In Stories of the Flemish & Dutch Artists, the author discusses how Rembrandt would attend art auctions, purposely overbidding, in order to “bring his own profession into better repute by showing that pictures and works of art were worth much more than people usually paid for them.” He would even purchase his own prints, “in order to stimulate public interest in them.” (Reynolds 212) These days, most everyone recognizes the name Rembrandt as an artist, even if they could not identify any of his paintings. His works were exceptionally good and he spent tedious hours perfecting every face in his elaborate, large-scale group portraits. Did Rembrandt’s “value schemes” during his lifetime benefit his posthumous fame? I like to believe it did. Either way, Rembrandt was broke when he died due to his addiction of purchasing art and antiques. This is anecdotal but it reminds me a bit of the way Nicolas Cage spent his fortune from the National Treasure franchise on a wide array of rare and unusual things, although Cage seems to be reinventing himself now.

Rembrandt, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1632)

Let’s look at another example. What do you consider the most famous painting in the world? I am sure you are thinking (or mouthing) “the Mona Lisa” right now. Did you know, before the 20th century, this painting was hardly mentioned in art history books? The quintessential Renaissance artist was considered to be Michelangelo while da Vinci was filed under the “sculpter” and “inventor” career categories rather than primarily a “painter.” Yet, the average person would have to think for a second to name off a work of art by Michelangelo.

Why is the Mona Lisa so famous? I have asked this of my high school students many times over the years. Some common answers I receive are:

“Her eyes follow you around the room.”

“Because it’s such a good portrait.”

“Because it’s mysterious.”

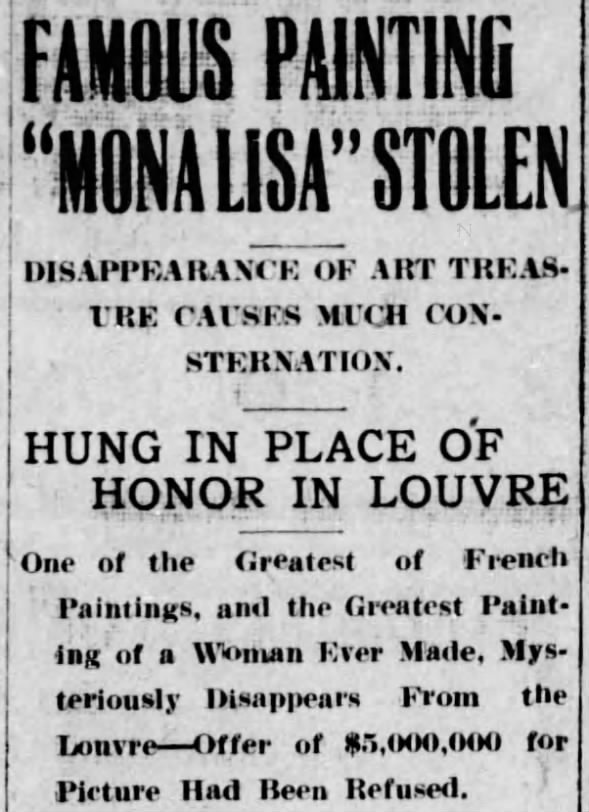

The problem is, none of these answers truly set it apart from any other well-painted portrait. What truly made this painting famous was the fact that it was stolen in 1911. Below is an article clipping that made it all the way to a South Carolina newspaper in 1911 describing the terrible heist of the beautiful and “famous” painting.

Famous Mona Lisa Stolen. Wed, Aug 23, 1911-Page 1. The Greenville News (Greenville, South Carolina). Newspapers.com

Now you might be questioning my knowledge about this painting since the article refers to the Mona Lisa as “famous” and “the greatest painting of a woman ever made.” However, let me explain. As a 21st century human, you probably are aware of how some videos and pictures go “viral” on the internet. Sometimes, it makes no sense. There’s no way to know what will gain traction and start trending and what will not. A similar case can be made for the Mona Lisa heist. It took an entire day for the Louvre museum staff to even realize that the Mona Lisa was missing. Once it was, French newspapers went wild and the fire spread from there (articles making their way outside of France, as the aforementioned South Carolina newspaper article demonstrates).

What is the moral of this story? I think there are a few things we can take from this. First, value in material items is a human construct, whether that means fame or in the monetary sense. There is no true measure of value.

Secondly, what determines our fame and success, beyond a level of hard work, is simply whether those in charge determine our work to be valuable. If a local news station starts discussing my art every night on the 6 o’clock news, that will lead to a higher level of value for my art. If the New York Times writes an article about my art, then the value of my art, and my artistic fame, are incredibly boosted.

I believe it is both a beautiful and terrible thing that this is how we can ultimately “make it” as artists. Regardless, it’s a good lesson for all practicing artists to remember this and it harkens back to my previous article discussing artistic business strategies.

I hope you enjoyed this week’s topic. Be sure to comment and share with someone who might enjoy these posts! You can follow me on instagram @ebofficialart to see my latest posts and learn more about the art world!

Works consulted:

Reynolds, Victor. Stories of the Flemish & Dutch Artists: From the Time of the Van Eycks to the End of the Seventeenth Century. Selected and Arranged by Victor Reynolds. United Kingdom: Chatto & Windus, 1908.