Exploring the “Starving Artist” Label

While painting, I often listen to podcast series or audiobooks. My interests range from biographical style podcasts about old Hollywood stars to wild sci-fi fiction to historical non-fiction to self-help related series. I know…it’s a wide variety but that’s the spice of life, right? One audiobook I listened to recently was Jeff Goins’ Real Artists Don’t Starve. In my efforts of pursuing an art career, I felt it would be beneficial to hear some art business strategies. I get a lot of backlash when I say I hope to pursue my art career fully in the future and I’ve got to say, it drives me crazy! This book introduced to me some interesting principles I never considered applying to the art world. I want to explore these ideas with you but first I want to focus on the origins of the saying “starving artists.” Why do we even say this? Where did it come from? Is it even true? Let’s take a journey through time and find out.

The year is 1845 and the setting is Paris, France. It is a bustling industrial city. French author Henri Murger has just published a story called Scènes de la vie de bohème, which translates to “Scenes from Bohemian Life.” Murger went on to publish a new story to add to this series roughly each year up until 1849. The stories feature four artists living in poverty-level situations in the Latin Quarter of Paris during the 1840s. Some of these characters were loosely based on real-life people that Murger knew. Despite their relatability and interesting commentary, the stories never reached a wide audience. So, in 1849, Murger asked the playwright, Théodore Barrière, if he would be interested in adapting the stories for a play. The play opened at the Théâtre des Variétés and became immensely successful. Eventually, Murger’s book was used as inspiration for operas by Puccini and Leoncavallo. Puccini’s La Boheme was extremely popular in the late 1890s and is considered by most opera-enthusiasts to be one of THE most famous operas of all time. Through this, the idea that artists must be “starving” was really solidified in our culture. However, one distinction I think should be made here is that these characters invented by Murger, Barriére, Puccini, and Leoncavallo lived this way, partly by choice. They were dedicating their lives to the art, sacrificing their wellbeing for the sake of art. Further, other literary experts interpret Murger’s “bohemian life” as simply a stepping stone to success. Read more about that here. It is the episode in your life in which you sharpen your craft. It wasn’t supposed to be viewed as a permanent stopping place.

Today, that nuanced distinction seems to be forgotten when we discuss the lives of artists. We have oversimplified the phrase “starving artist” to mean it is never going to be a lucrative career. However, I ask that you consider Murger’s own literary journey. He wrote interesting stories that he knew could have an impact on society. However, after finishing publishing the stories, he didn’t really see much success (at least, not until he collaborated with Barrière). With any business, with any living we want to make, we have to market as much as create. Let me explain a little further.

Let’s say you are talented chef. You take out a loan to open a small restaurant in your town. Your friends and family rave about your skills as a chef and you know that your customers will love your food too. So, you pump all your energy in decorating the restaurant, getting the proper licenses, and crafting a perfect menu with reasonable prices. You believe, “if I build it, they will come.” You wait for people to arrive. No one ever comes. Why? You never took time to advertise. You never told people about your restaurant (beyond your friends and family) so how would anyone know what you have to offer? No one knows why your restaurant is special.

With any entrepreneurial business, one must balance the art with the marketing side of things. Dedicating yourself too much to one side can lead to the demise of your business. The starving artist mythos exists because the artist wasn’t and/or didn’t want to be business-minded.

In Real Artists Don’t Starve, Goins discusses the following strategies to ensure your art business is successful:

Steal from your influences (don’t wait for inspiration)

Collaborate with others (working alone is a sure fire way to starve)

Take strategic risks (instead of reckless ones)

Make money in order to make more art (it’s not selling out)

Apprentice under a master (a “lone genius” can never reach full potential)

Stealing from Your Influences

Stealing from your influences does not mean total plagiarism. Rather, Goins explains that no ideas happen in a vacuum. As humans, we are constantly taking inspiration from everything around us. We can do that too from our favorite artists, as long as we don’t totally copy their work and that we do give credit where credit is due. One artist from my home state of Alabama that I believe follows this strategy exceptionally well is Butch Anthony. You can see more of his lifelong work by clicking here.

This is a Butch Anthony piece hanging in Knucklebones Elixir Co. in Mobile, AL.

As you can tell by looking at his work, he takes prints, original paintings, and old photography (including some that are widely recognizable), but adds a unique distinction by drawing and overlapping new features. It puts me in the mind of Marcel Duchamp’s Dadaism work. He was the first to officially put a mustache on the Mona Lisa.

Marcel Duchamp, 1919, L.H.O.O.Q.

The Dadaism movement is very fascinating and I will definitely explore this topic more with you in a future post.

Collaborate with Others

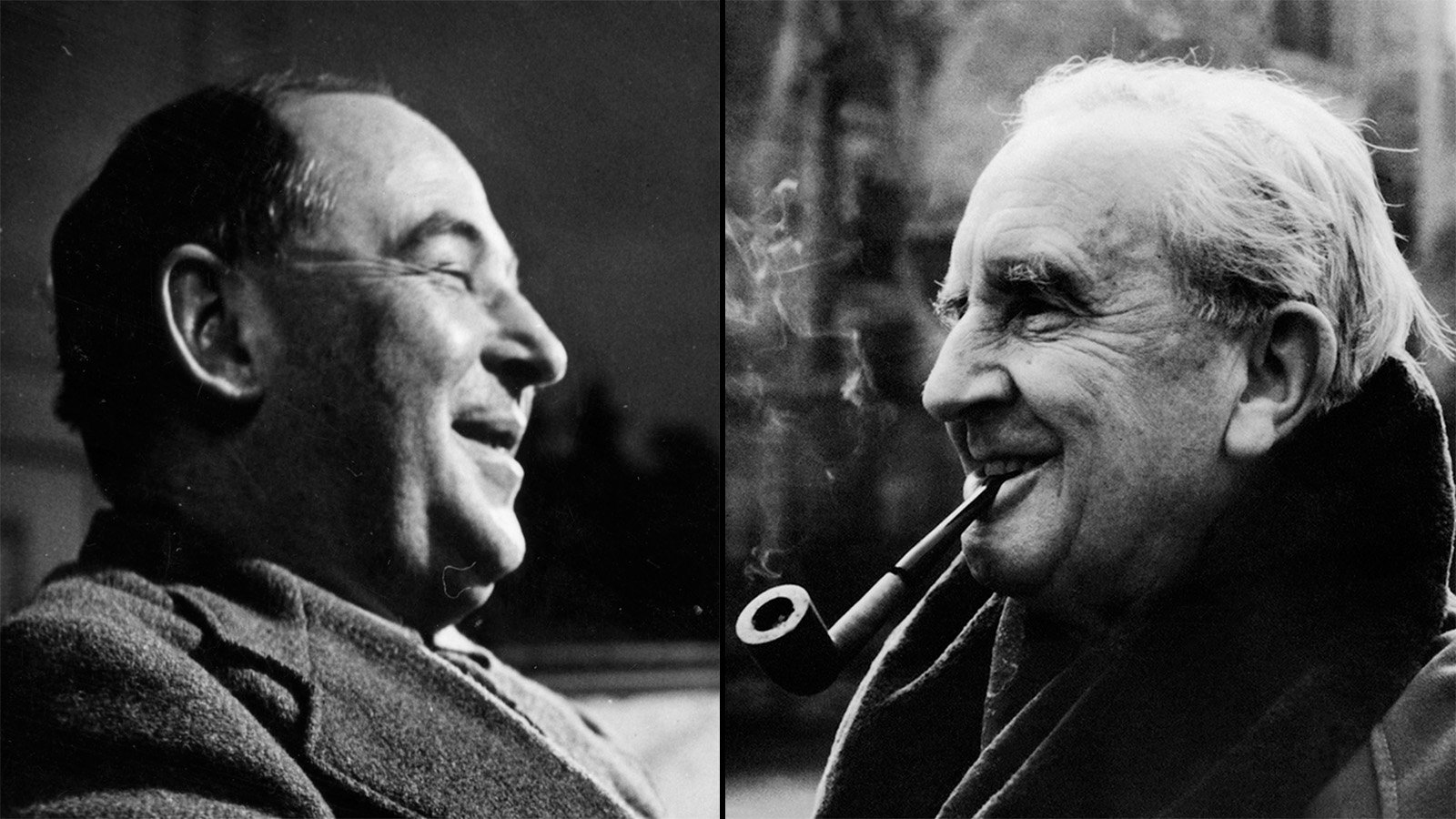

Collaborating with others especially spurs creativity, motivation, and exponentially expands your ability to advertise. Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin actually lived together at one point in order to collaborate. Though the living situation was rather volatile, they took inspiration from one another and helped to generate a new genre of art—post-impressionism. Pablo Picasso was known for surrounding himself with artist friends. JRR Tolkien and CS Lewis had weekly “writing chats.” Mary Shelley and her friends had a writing challenge and she produced Frankenstein through this. I have even seen the power of this sort of collaboration first hand.

CS Lewis and JRR Tolkien are pictured above.

When my art teacher colleagues and I travelled to New York City with each other for an art conference, we spent the evenings excitedly discussing new ideas and strategies. It was incredibly refreshing and fun. One example of our collaboration is our annual black light exhibition on our school’s campus. It attracts a lot attention in the local community and it is such a fun way to get more students (and adults) interested in art. Imagine having like-minded friends or colleagues who can help you reach new heights with your creativity that you could meet with regularly. It is so powerful.

The 2022 Black Light Exhibition at FHS

So, if you’re struggling to find collaboration, join your local art community (there are usually clubs or councils you can be part of). If no art community exists where you live, MAKE ONE. You will need to seek out opportunities for yourself. Most of the time, they won’t magically find you. Apply for grants. Apply for art shows. Apply for competitions. You must carve out time in your art working days to simply do those tasks. I have done this in my own career and it generates a snowball effect. One example is my application to the Artrepreneur NYC show and another is the September 16 Mobile Arts Council Artist Throwdown Competition. I know this will be an incredible opportunity to have my art shared with a wider community! Plus, I get to meet a whole new group of artists who I can potentially collaborate with in the future.

Take Strategic Risks

Taking strategic risks is an interesting point of Goins. The impulse in the art world is to devote yourself wholeheartedly and unabashedly to developing your art, i.e. see what I said about the context of the “starving artist” above. This is not always wise though. You must first develop a name and reputation for yourself before you can totally free yourself to that work. The hard part about this one is that it means a lot of extra work for awhile. It means keeping your day job until your art career can take off. I do think something can be said for picking a day job that is minimally stressful or less strenuous so that you have more physical and mental energy to devote to your art though. That most likely will mean less pay, but if you can make it work, look at it as a stepping stone to your ultimate goal just as Murger intended with his Scenes from Bohemian Life.

Make Money in Order to Make More Art

We often view artists who are in it for the money as not being “authentic artists” but that myth must be dispelled! Artists spend years refining their skills, like other professionals, and deserve to be paid adequately. Don’t minimize or undersell your work. If you find yourself questioning the money, just remember this is your career and this is how you support yourself. You also must remember that it can take time for original pieces of art to find homes. Bigger, more elaborate, and expensive pieces take longer to sell. In the meantime, you should sell prints of your work. This has been a real money maker for me and you can think of it as a form of advertisement of your work in hundreds of homes. Though this is up for debate in the art community, I do think more prints of a work of art increases the value of the original painting.

Apprentice Under a Master

Apprenticing under a master goes hand-in-hand with the collaboration point. I believe it can open many doors for an aspiring artist and make an artist think in ways not considered before. These days, I hear more and more people criticize those individuals who go to school for art as pursuing something that is a “useless degree.” However, if you attend a more prestigious art college, then one of the most important things you can take from that experience is networking and learning from true masters of art. This is one point that I struggle with personally. As someone who never received a formal degree in art, I did not have the opportunity to study under a master. I do think if I continue pursuing the other points Goins makes though, this point might become more feasible in the future. So, if you struggle like I do with this, make sure you do all four of the other points really well and I bet you will be surprised where it leads you.

Jeff Goins goes on to share MANY more useful tips and strategies but obviously if you are interested, at this point, you just need to read the book for yourself! I truly believe every aspiring artist should own a copy. As an art educator, I hope business strategies are something I can incorporate more into my teaching in the future.

Finally, I want to leave you with some statistics.

Artist Net Worth (now or upon death)

Pablo Picasso $250 million-$1 billion (why such a wide range? It’s an interesting story, read about it here: https://www.vanityfair.com/culture/2016/03/picasso-multi-billion-dollar-empire-battle )

Margaret Keane $50 million

Andy Warhol $220 million

Jackson Pollock $5 million (in 1956 money)

George Rodrigue $11 million

Damien Hirst $384 million

Yayoi Kusama $20 million

Jeff Koons $400 million

Jasper Johns $300 million

David Choe $200 million

The American Community Survey (ACS) estimates there are 1.4 million practicing artists in the US. Of this, only about 200,000 (10%) of that make their primary earnings as working artists. The median salary is $30,000 for artists in the US. While that might be discouraging, consider that thAt is the equivalent of selling 250 products for $120 a piece. That breaks down to selling 20-21 products a month. How much time are you putting into each of these products? One hour per product? If so, that is the equivalent of getting paid $120 an hour which is quite good. Where is there room for growth? Could you increase the price or make more products? The salaries clearly have a wide range based on the net worth examples I have shared from 20th and 21st century artists above. I believe artists also do not consider the wide variety of options now. Simply selling artwork is not the only outlet.

One particular artist I would like to highlight is David Choe. He is currently 46 years old and if you look at his Wikipedia page, the description of him begins as, “…an American artist, musician, and former journalist and podcast host from Los Angeles.” I share this because Choe dedicated himself to wearing many different hats in the pursuit of his art. His first graphic-novel was actually self-published and he gave out copies for FREE at the Los Angeles Comic Con in 1998 in hopes of catching the interest of a publisher. Remember what I said earlier about CREATING your own opportunities? In 2008, he co-created a documentary about his life. Eventually he was scoring commission works from prominent celebrities and business owners.

In this day and age, you must be a self-promoter and look for opportunities at all times. You must want and believe your career will succeed and it will.

Did you find this helpful? What successful entrepreneurial stories do you find especially inspiring? I would love to hear from you! Share a comment below. Be sure to subscribe to keep up with my latest blog posts. Follow me on instagram @ebofficialart to see all my latest art and learn a bit of art history.

Books Referenced:

Goins, Jeff. Real Artists Don't Starve: Timeless Strategies for Thriving in the New Creative Age. New York: HarperCollins Leadership, 2018.

Murger, Henri. The Bohemians of the Latin Quarter. United States: L. C. Page, 1906.